North Korean Konni Group Targets Blockchain Developers with AI-Generated PowerShell Malware

The North Korean cyber espionage group known as Konni has recently intensified its operations by deploying AI-generated PowerShell malware to infiltrate blockchain development environments. This sophisticated campaign has expanded its reach to target developers and engineering teams in Japan, Australia, and India, marking a significant shift from its previous focus on South Korea, Russia, Ukraine, and various European nations.

Background on Konni Group

Active since at least 2014, Konni has a well-documented history of targeting organizations and individuals, primarily in South Korea. The group is also recognized under aliases such as Earth Imp, Opal Sleet, Osmium, TA406, and Vedalia. Their operations have consistently evolved, demonstrating a persistent and adaptive approach to cyber espionage.

Recent Developments

In November 2025, the Genians Security Center (GSC) reported that Konni exploited Google’s asset tracking service, Find Hub, to remotely reset Android devices, effectively erasing personal data. This tactic signified a notable escalation in their cyber capabilities.

More recently, Konni has been observed distributing spear-phishing emails containing malicious links disguised as legitimate advertising URLs associated with platforms like Google and Naver. This method effectively bypasses security filters, facilitating the delivery of a remote access trojan known as EndRAT. Dubbed Operation Poseidon by the GSC, these attacks impersonate North Korean human rights organizations and financial institutions in South Korea. The campaign is characterized by the use of poorly secured WordPress websites to distribute malware and establish command-and-control (C2) infrastructure.

Attack Methodology

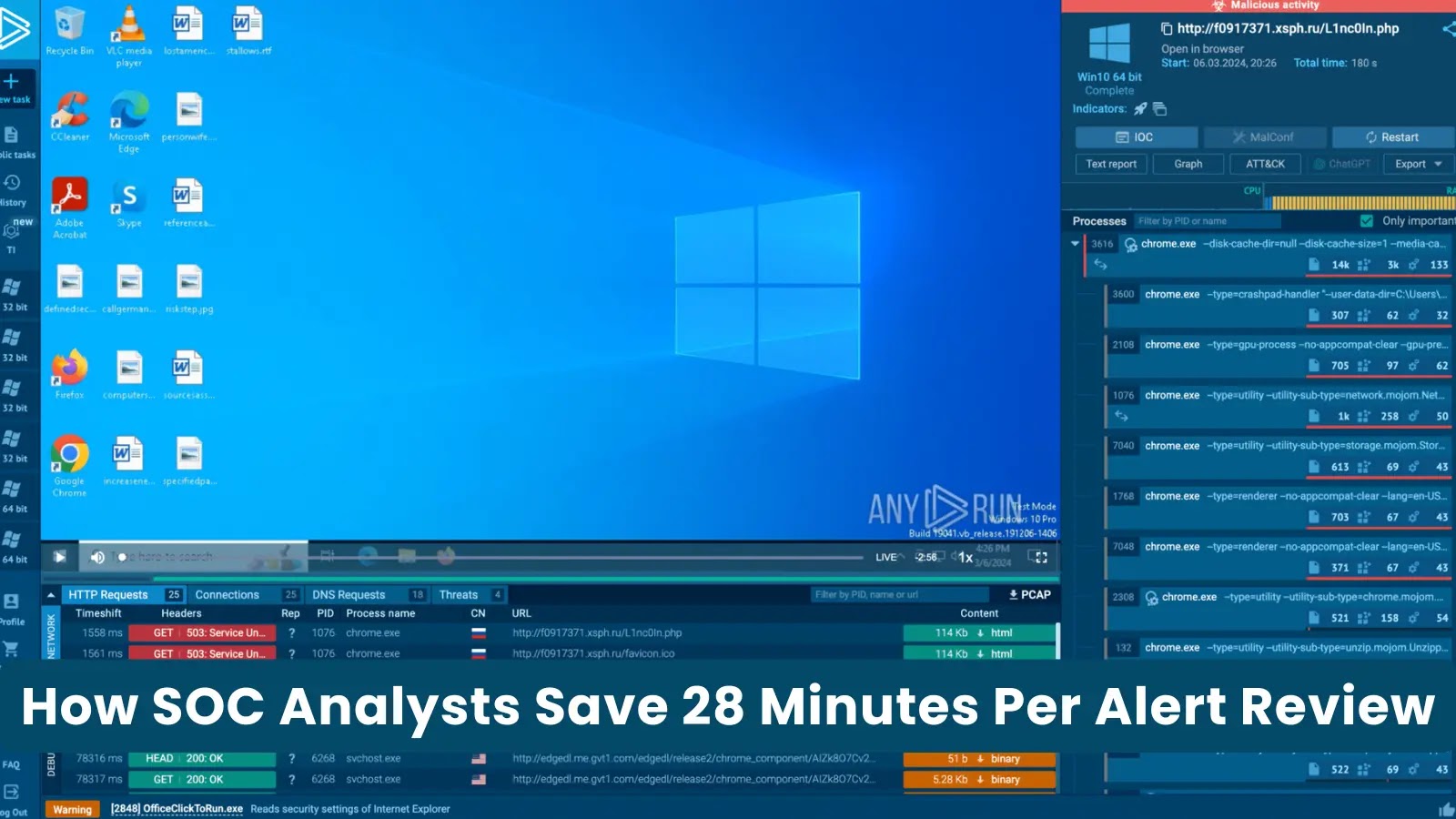

The latest campaign, as detailed by Check Point Research, employs ZIP files masquerading as project requirement documents hosted on Discord’s content delivery network (CDN). The exact initial access vector remains unidentified, but the attack sequence unfolds as follows:

1. ZIP Archive Contents: The archive includes a PDF decoy and a Windows shortcut (LNK) file.

2. Execution of LNK File: Activating the shortcut initiates an embedded PowerShell loader, which extracts two additional files—a Microsoft Word lure document and a CAB archive—and displays the Word document to distract the user.

3. CAB Archive Extraction: The shortcut extracts the CAB archive’s contents, comprising a PowerShell backdoor, two batch scripts, and an executable designed for User Account Control (UAC) bypass.

4. Batch Script Execution: The first batch script prepares the environment, establishes persistence via a scheduled task, stages the backdoor, and executes it. Subsequently, it self-deletes to minimize forensic traces.

5. PowerShell Backdoor Operations: The backdoor performs anti-analysis and sandbox-evasion checks, profiles the system, and attempts to elevate privileges using the FodHelper UAC bypass technique.

6. System Cleanup and Persistence: The backdoor cleans up the previously dropped UAC bypass executable, configures Microsoft Defender exclusions for C:\ProgramData, and runs the second batch script to replace the initial scheduled task with a new one capable of running with elevated privileges.

7. Deployment of Remote Monitoring Tool: The backdoor deploys SimpleHelp, a legitimate Remote Monitoring and Management (RMM) tool, for persistent remote access. It communicates with a C2 server protected by an encryption gate designed to block non-browser traffic, periodically sending host metadata and executing PowerShell code received from the server.

Indicators of AI Utilization

Check Point Research suggests that the PowerShell backdoor exhibits characteristics indicative of AI-assisted development. These include a modular structure, human-readable documentation, and source code comments such as # <– your permanent project UUID. This implies an effort to accelerate development and standardize code while continuing to rely on proven delivery methods and social engineering tactics. Strategic Implications Unlike previous campaigns targeting individual end-users, this operation appears focused on establishing footholds within development environments. Compromising these environments can provide broader downstream access across multiple projects and services, amplifying the potential impact of the attack. Broader Context These findings align with other North Korean-led campaigns aimed at facilitating remote control and data theft. For instance, a spear-phishing campaign utilized JavaScript Encoded (JSE) scripts mimicking Hangul Word Processor (HWPX) documents and government-themed decoy files to deploy a Visual Studio Code (VS Code) tunnel for remote access. Another campaign distributed LNK files disguised as PDF documents to launch a PowerShell script capable of detecting virtual and malware analysis environments, subsequently delivering a remote access trojan named MoonPeak. Additionally, two cyber attacks attributed to the Andariel group in 2025 targeted a European legal entity to deliver TigerRAT and compromised a South Korean Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) software vendor's update mechanism to distribute new trojans, including StarshellRAT, JelusRAT, and GopherRAT. Conclusion The Konni group's adoption of AI-generated malware signifies a significant evolution in cyber threat tactics, particularly within the blockchain sector. This development underscores the necessity for enhanced vigilance and robust security measures among developers and organizations operating in this space.